© WaSHI

Ask a Soil Scientist: Liming and Basalt

Have a burning soil health question? You’re in luck! WaSHI has a team of expert soil scientists who can answer some of the most challenging soil science questions.

February 26, 2025

Author: Adam Peterson

For our first Ask a Soil Scientist blog post, WSDA Agronomist Adam Peterson speaks with a farmer from western Washington about their soil pH and the potential use of basalt dust.

Question: We’re trying to raise our soil pH (currently 5.1) and are interested in using basalt dust. What application rates do we need and would it be effective?

Response:

Thanks for reaching out and that’s a great question! Just like your soil test results showed, soils in western Washington tend to run on the acidic side.

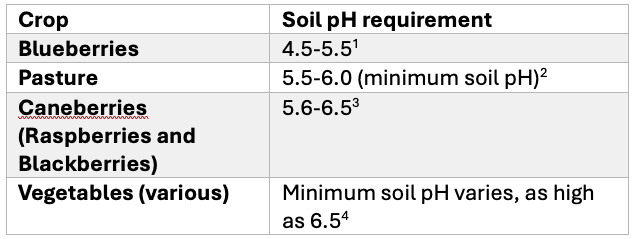

While some crops in western Washington love the acidic soils (e.g., blueberries), others prefer a less acidic or even neutral soil pH. See Table 1 for soil pH of some commonly grown crops.

Table 1. Preferred soil pH for common western Washington crops.

To raise soil pH for crops that need it, many farmers in western Washington regularly add a liming agent to their soil, typically agricultural lime.

There is growing interest in using basalt as a liming agent for many reasons: 1. Unlike conventional liming materials, basalt dust is often a byproduct of other mining operations and therefore can be a more environmentally friend option, and 2. When added to certain soils, basalt can actually draw down atmospheric carbon dioxide, thereby helping mitigate climate change

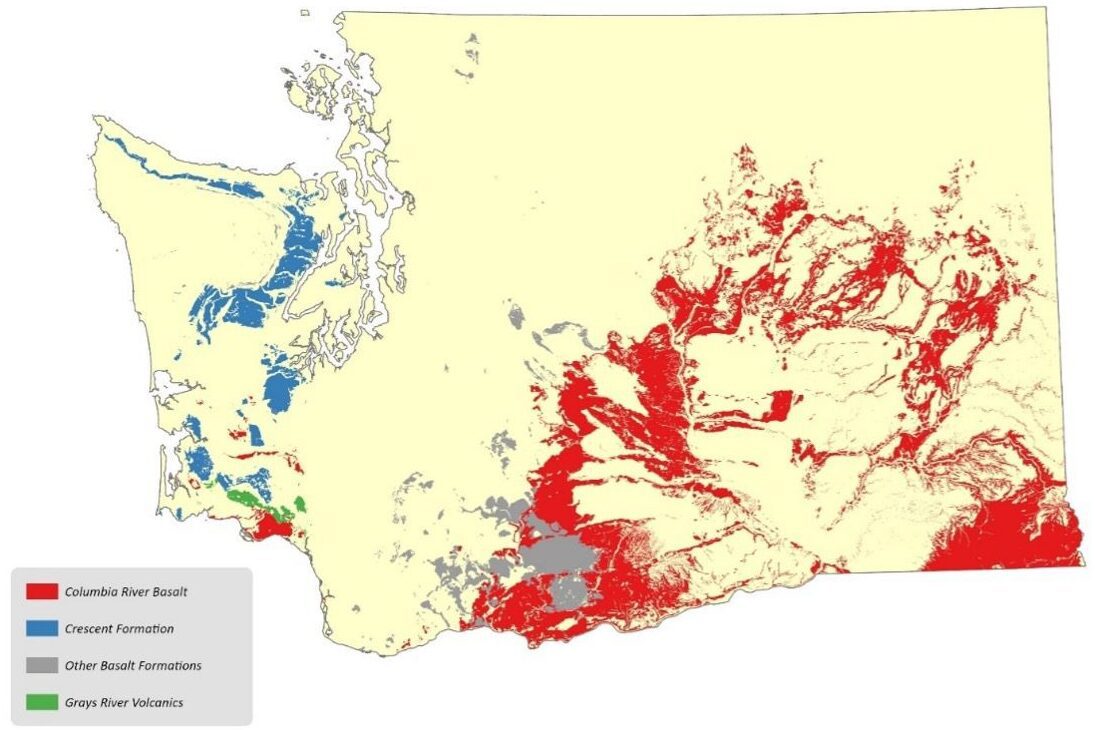

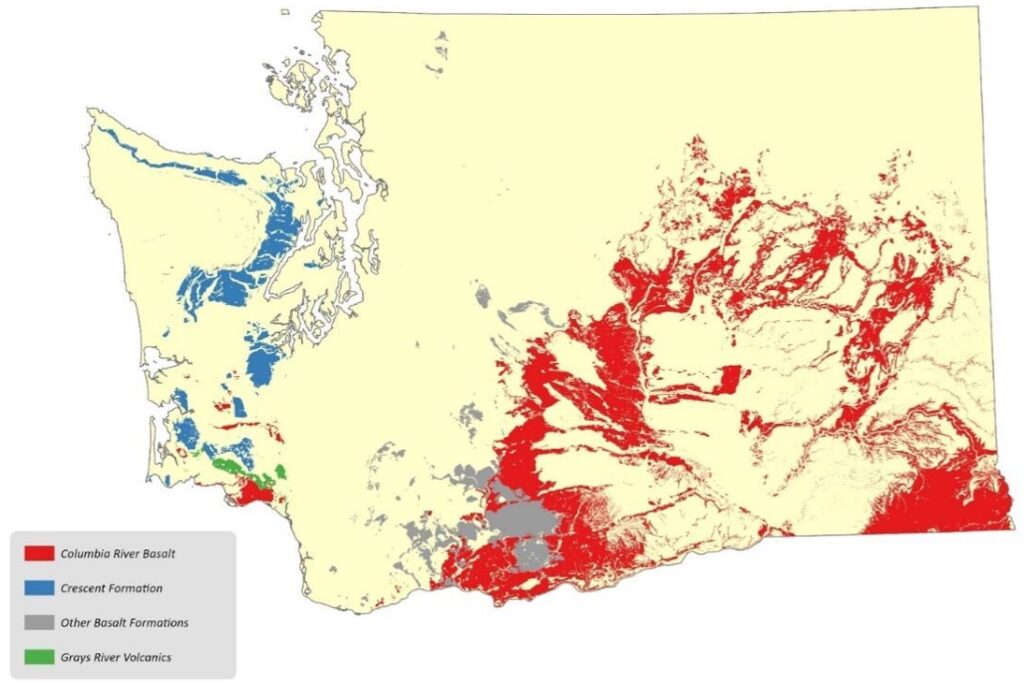

Here in Washington, we have a lot of basalt on both sides of the Cascades! Your local quarry is likely mining basalt from the Crescent Formation, common throughout western Washington and shown in blue in the map below.

Figure 1. Basalt formations in Washington state (Data credit: WA DNR).

Buffer Index

Let’s start by determining your liming agent requirement. The key figure here is the “Buffer Index” or “Buffer pH”. This number, combined with your soil pH, helps determine how resistant your soil is to changes in soil pH. In that test, a standardized solution is added to a soil which raises soil pH, just like a liming agent would.

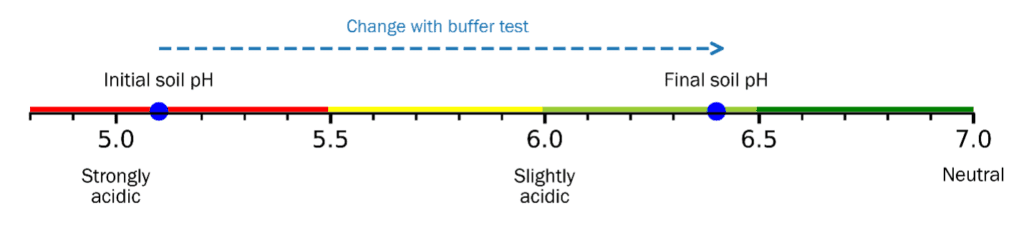

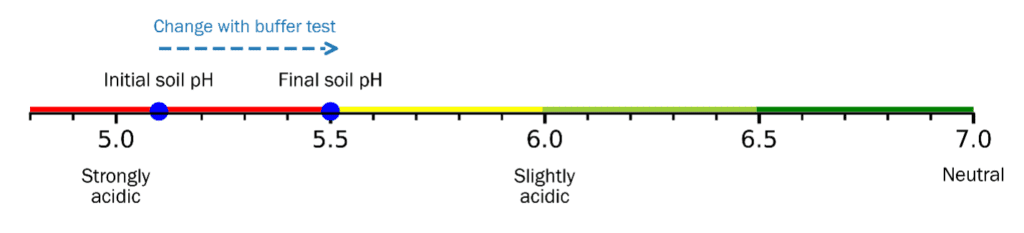

Let’s visualize this for two different soils with the same pH, but different Buffer Index values.

In this graphic below, the soil pH changes from 5.1 to 6.4 – a considerable change. This is considered a “weakly buffered” soil.

With a strongly buffered soil, the same solution only changed the soil pH from 5.1 to 5.5, a much smaller change. A soil like this would need much more liming agent to reach a target pH than a weakly buffered soil.

Your current soil pH is 5.1 and buffer index is 6.3, which means you have a weakly buffered soil.

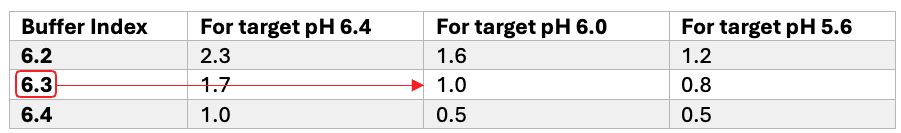

Below is a chart from OSU for the particular test your soil test lab ran (the Sikora buffer). Let’s choose a target soil pH of 6.0 – a good target for many vegetables. Following the chart, you would need 1.0 tons of limestone per acre. While a ton sounds like a lot, it’s a fairly modest application rate for limestone.

Lime Score

Limestone’s ability to raise soil pH is measured by its “Lime Score”. The table above provides recommendations for 100-score lime. If you’re working with a limestone with a higher or lower lime score, you’ll need to adjust the rate. To do this, simply multiply the liming requirement by 100 divided by the lime score.

For a 70-score lime, you would make the following adjustment:

1 ton lime (100-score)/acre x (100/70) = 1.42 tons limestone (70-score) per acre

And for a 107-score lime, that adjust would like the following:

1 ton lime (100-score)/acre x (100/107) = 0.93 tons limestone (107-score) per acre

How much basalt dust is needed?

By multiplying this limestone requirement by basalt’s LE (lime equivalence) number, we can determine how much is needed.

The only readily available source of basalt’s LE is from North Carolina State University. They estimate basalt has a LE of 35, resulting in a basalt requirement of 35 tons per acre. That is a lot of basalt! Applying more than 2 tons limestone per acre can smother pastures, so for situations where incorporation through tillage isn’t possible, powdered basalt may not be ideal. Basalt also contains many micronutrients, so you’d want to be careful not to raise certain elements to toxic levels.

Important differences

Just like there are different types of limestone, there are differences in the mineralogical makeup of different basalts, including those in Washington state7,8. There are also factors like climate and grind fineness that could influence how quickly basalt reacts with your soil.

With all these unknowns, it’s difficult to say how much basalt dust would change your soil’s pH. We don’t yet have something akin to a “Lime Score” for basalt. More research is needed!

If you do try basalt dust, consider starting small and in fields where tillage can allow you to incorporate the large quantities needed. Soil testing, both before and one year after application, can help you track changes in soil pH and other nutrients. Try testing the same time each year to eliminate seasonal fluctuations in soil pH. Soil pH tends to be at its least acidic in late winter/early spring, and most acidic at the end of the growing season9.

For a less experimental approach, agricultural limestone is always a dependable option and readily available.

Submit a question to our Ask A Soil Scientist page and the answer may be featured in the WaSHI blog series and newsletter!

References

- Hart, J. M.; Strik, B.; White, L.; Yang, W. Q. Nutrient Management for Blueberries in Oregon; EM 8918; Oregon State University Extension, 2006; p 21. https://extension.oregonstate.edu/sites/extd8/files/catalog/auto/EM8918.pdf.

- Moore, A.; Pirelli, G.; Filley, S.; Fransen, S.; Sullivan, D.; Fery, M.; Thomson, T. Nutrient Management for Pastures: Western Oregon and Western Washington; EM-9224; Oregon State University Extension, 2019; p 16. https://extension.oregonstate.edu/sites/extd8/files/documents/em9224.pdf.

- Hart, J.; Strik, B.; Rempel, H. Nutrient Management Guide: Caneberries; EM 8903-E; Oregon State University Extension, 2006; p 8. https://extension.oregonstate.edu/sites/default/files/documents/em8903.pdf (accessed 2024-07-02).

- Sullivan, D. M.; Peachey, E.; Heinrich, A. L.; Brewer, L. J. Nutrient Management for Sustainable Vegetable Cropping Systems in Western Oregon; EM 9165; Oregon State University Extension, 2017; p 25. https://extension.oregonstate.edu/sites/default/files/documents/em9165.pdf.

- Amann, T.; Hartmann, J. Carbon Accounting for Enhanced Weathering. Front. Clim. 2022, 4, 849948. https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2022.849948.

- Moore, A. Updated Lime Requirement Recommendations for Oregon. Ag - Forages/Pastures. https://extension.oregonstate.edu/sites/extd8/files/documents/9276/new-sikora-based-lre-recommendations-osu-moore-040622.pdf (accessed 2025-01-22).

- Sadowski, A. J.; Becerra, R. I.; Toth, C. H.; Polenz, M.; Anderson, M. L.; Lau, T. R.; Nesbitt, E. A.; Tepper, J. H.; DuFrane, S. A. Geologic Map of the Adna 7.5-Minute Quadrangle, Lewis County, Washington; Map Series 2019-01; 2019.

- Polenz, M.; Toth, C. H.; Samson, C.; Sadowski, A. J.; Becerra, J.; Lau, T. R.; Anderson, M. L.; Nesbitt, E. A.; Tepper, J. H.; DuFrane, J. H.; Legoretta Paulin, G. Geologic Map of the Rochester 7.5-Minute Quadrangle, Thurston and Lewis Counties, Washington; Map Series 2019-02; 2019. https://www.dnr.wa.gov/publications/ger_ms2019-02_geol_map_rochester_24k.zip.

- Horneck, D.; Hart, J.; Stevens, R.; Petrie, S.; Altland, J. Acidifying Soil for Crop Production West of the Cascade Mountains; EM 8857-E; Oregon State University, 2004; p 11. https://s3.wp.wsu.edu/uploads/sites/2056/2023/05/Acidfying-Soil-for-Crop-Production.pdf.

Adam Peterson

Agronomist at Washington State Department of Agriculture

This article was published by the Washington Soil Health Initiative. For more information, visit wasoilhealth.org. To have these posts delivered straight to your inbox, subscribe to the WaSHI newsletter. To find a soil science technical service provider, visit the Washington State University Extension website or the Washington State Conservation District website.